[Having been promised tech support by the Bar’s IT / AV expert, I prepared my presentation on my IPad. As you will see it includes some photos and scans, downloaded and borrowed (for non-profit purposes, I assure any copyright holders). Unfortunately, the AV “expert” had not counted on my limited tech expertise when he had assured me that the wireless connection of my IPad to the video screen would be “no problem.” Now, he revealed that this new system hasn’t been used much before. And I as it turned out, it was not very useful to me.]

All of which explains (but as in capital case mitigation, fails to excuse) my hurried and disjointed performance. Like closing arguments, it is sadly true that you give three: the one you prepared, the one you actually gave, and the one you recite in your mind on the way home and repeat over and over again in regret. This blog has served as my soapbox since my son suggested it several years ago and now this post will I hope be something of a final argument for me.

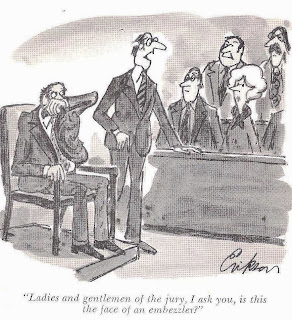

So as I promised those who attended, here is the fuller presentation, with cleverly gathered “slides” to illustrate the brilliant points I tried to make. This is the talk I wanted to give.

“Taking Losses

aka “The Art of Losing”

aka “Surviving Losses”

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster...

Elizabeth Bishop

Neither the title nor its alternates are satisfactory to me. I am not trying to help lawyers to lose their cases. (They are capable of doing that on their own.) Not even trying to make them accept losing. But rather, one of my goals is to give ammunition so that they will not be discouraged by the possibility or even the probability of losing.

It is a fact of life that the appointed criminal defense lawyer is likely to “lose” far more cases than he or she “wins.”**

** [It must first be noted that the words “lose” and “win” are deceptive. For the appointed criminal defense lawyer wins and losses are relative terms. As an example, one of my early role models was Charlie Gessler, a legendary L.A. Deputy Public Defender. In my early days in the office, Charlie was a “heavyweight,” trying the toughest, most serious cases.]

For instance, he defended the fellow called by the press, “The Skid Row Slasher,” title enough to suggest what Charlie was up against. Each day of the trial, he faced the ever more gory details, the mounting evidence against his client. Each noon he would come into the lunchroom with his styrofoam coffee cup and sandwich and chew while taking a ribbing from the lawyers arrayed around the table.

“How’d it go today, Charlie?” From the snickering gadflies, none of whom envied Charlie his daunting task of being pummeled into dust each day.

Charlie shrugged, said in his usual grave yet calmly enthused voice: “Had a good morning. Think I developed an argument on the ‘use allegation’ in count twenty-six.”

That is the kind of sturdy toughness we all would feel blessed to attain. Charlie knew that a “win” might be getting one count dismissed, or one enhancement, or merely (as Hemingway might put it) “dying well.”

THE FEAR OF FAILURE One of the biggest causes of burnout among our breed is the fear of failure.

For people who are said to be confrontational and contentious by inclination and by training, I have found that many of my peers actually are terrified of going to trial.

Whether this is a matter of ducking a crucible, a revealing test of their talent, skill, judgment . . . Or a perceived risk to their self-esteem, or some other deep character flaw, I will not judge. The fact is that many will duck — possibly at the last moment — they will blink, avoid the risk and take a deal (ironically as you will see if you continue to read — “against their better judgment”). And they may well feel miserable afterward.

I know all of this because I must now admit to the world that I have felt this crushing weight many times during my career. Night sweats, headaches, grinding teeth, mental constipation for days on end — all in dread anticipation of an oncoming trial — and the humiliation of another loss. (The feeling, I have learned when describing it to acquaintances, is not unlike the stage fright that confronts actors). The fear of rejection, embarrassment, ridicule, exposure as “a loser” is often more than one can bear. At this late stage in my professional life I want to “give back” by sharing the fruits of my reflection.

A WASTED LIFE? Another motivation for my giving this lecture comes from a talk with a friend who is recently retired. He admitted to me that he hated his five years as a public defender almost as much as he hated the next thirty-five years he spent in private criminal practice.

“I chose the wrong profession. At least the wrong side. I loved football, all sports. What I wanted in a career was competition. At first, and later, there were times I liked the gamesmanship, the kick of putting something over on the opponent. But I couldn’t stand losing. Honestly, I never really cared about my clients, I cared about winning. It was me against the world, and the clients were part of the world. I hated what I did for a living. It was all bull____.”

So much for the romance of “The Lost Cause.” Was my friend right? Is it all just a game? Did I accomplish anything worthwhile in forty-three years of practice? Is it a profession or just a sleazy way of milking money from frightened people and / or a foolishly spendthrift government?

To put the question starkly: Did I (Gulp!) live a wasted life?

For years, since my son urged me to put my thoughts in order, I have been posting observations on this blog. Often I have posed questions and tried to provide answers to conundrums that have haunted me during my career.

Recurring questions from friends or lovers: “Why do you defend these people?” “How can you defend someone you know is guilty of horrible crimes?” “How can you sleep at night after getting some heinous criminal off?”

From colleagues, the oft repeated head shaking shoulder shrugging complaint: “Why do our clients do stupid things that screw up our cases?” “What’s the use of caring when it is all so futile?”

It seemed to me that if I could make some sense out of those issues I might have some sort of peace of mind about my profession, maybe even feel good again and relate that experience to my colleagues so that the poor fools might survive better than I have.

You see, when I began, I thought it was a wonderful idea, to defend people against the weight of the all-powerful powers (whoever “They” might be). Looking back, this seems so naive as to be infantile, a child’s fairy tale or a construct of left wing bleeding heart writers in Hollywood.

I was raised on the myth of the defense lawyer as hero. My father told me stories about those of his youth: Clarence Darrow against capital punishment (Leopold and Loeb); Sam Leibowitz, who defended the Scottsboro Boys (and then became, to my father’s shame, a “hanging judge”). T.V. provided other examples, some caricatured (“Perry Mason”) and others more serious (“The Defenders”). In school we read “To Kill A Mockingbird” and “Intruder In The Dust.”

To a Jewish kid raised in Brooklyn in the 1950's, siding with the underdog was natural. A childhood spent watching the Dodgers (vs. the Yankees, the “evil empire”) and living with the mantra: “wait ‘til next year”was good preparation for a life of “fighting the good fight” and “losing with dignity.”

This myth was reinforced by romantic movies. “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington” — Jimmy Stewart: “The lost causes are the ones worth fighting for.” And “Casablanca” with Bogart “I’m not too good at being noble. . .”

But it doesn’t take long for the reality to bury the myths. Losing takes a dreadful toll. You begin to doubt your talent, skill. Even when you “win” — an argument, or a case — you find that your elation is short-lived. Your main emotion is relief. You know that it is an anomaly. Soon the losses hurt more than the wins feel good. The wounds caused by the lows aren’t healed by the salve of the wins. The result is stress . . . Depression . . . Burnout.

| Themis at Old Bailey |

Some begin with elevated expectations. Blind Justice with its double edged sword and even scales promising "equal justice under law" misleads.

Others soon cave in to lowered expectations. They yield to The Law of the Roller Coaster: If you are handed a bad case, no matter how high your hopes may soar, you will always end up where your start: with a loser.

I remember that in college, I had read about the causes of stress in my Psych I class. The experiment of the “Executive Monkeys” proved that stress could kill.

| Rhesus monkeys tortured for "science" |

I came across a corollary to this rule in college, when learning another important skill — how to win at blackjack in Las Vegas. Professor Edward O. Thorp’s “Beat The Dealer” proved that there was a right way to play the game. Even if the cards you are dealt give you a low probability of winning a hand, you should still play it in a manner that maximizes your chances. But you should reduce your expectations when dealt the bad hand. Don’t rail at the Fates.

The realistic recognition that the odds are against you but that you can still win a share can be uplifting. The baseball analogy, though trite, does apply. If you bat .300 for a career, it means you have failed seven of ten times at bat, but you will be in the Hall of Fame.

My retired friend couldn’t handle the stress of always being on the defensive. Good lawyers are naturally argumentative, competitive, aggressive. But defending, especially the appointed criminal defendant, usually requires a more deft touch. We rarely have strong, righteous affirmative legal defenses; we usually rely on the flaws in the prosecution case — it is bad practice to urge “innocence” rather than the more subtle distinction of “not proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.” We are rarely in the Perry Mason position of forcefully attacking a witness / victim on the stand.

Representing the appointed criminal defendant has stresses over and above that of defending the client who has paid for your services. There is a natural suspicion that what you receive for nothing defines its worth. Your are suspected of being in the pocket of the authorities, the same people who pay the salaries of the judge and prosecutor. Acceptance of the appointment is rarely based on the likelihood of a win which may or may not be the case of taking on a private client.

At any time during the case, the client may go off on the lawyer. If in jail, he is influenced by jailhouse lawyers advising him on the side. If out, he may be searching the internet for loopholes. He demands:

“Why don’t you file a motion of search and procedure?” “How about a pitcher’s motion?” “I want my (sic) trans Crips!”

Your skills at “client control” will be tested throughout, forced to field existential questions: “Do you really believe in my innocence?”

When I candidly related to a capital client how strong the prosecution’s case was, he asked: “Are you on my team?” I said, “Not if your team will be executed!”

To add to the problem, clients will often do everything they can to gum up the works. They will present you with a hopeless set of facts caused by their actions and will be angry that you cannot work magic and make it go away. When you find a reasonable way out, chances are they will do something more to screw it up: threaten a witness, pick up a new beef, get thrown in “the hole” for fighting an inmate or assaulting a deputy sheriff.

FRIENDS AND LOVERS After your hard day at work, you may return to your home where you will be confronted by your loved ones.

“How was your day, darling?” Your significant other will ask.

You may grumble, unwilling to re-hash the misery of the day. You just want to make love, eat, drink, relax.

“But we never communicate.”

You sigh, this is dangerous. But how do you start. “I lost a 995 (or 1538.5).”

A quizzical look. “Remind me.”

You explain — again, about these “technicalities.” “Hours of research. I wrote a terrific P&A. The D.A. never responded, the judge didn’t bother to read it. Just denied, denied.”

A sympathetic hug, but then the look. “But darling, your client was really guilty, anyway, wasn’t he?”

At family gatherings you are reminded that your parents, though proud when you passed the Bar Exam and were sworn in, sometimes let their friends believe that you prosecute rather than defend criminals.

When friends or mere acquaintances (many of mine were civil lawyers, doctors, and their spouses) ask the nasty questions, I tried various strategies, depending on my state of sobriety, my patience, etc.

“How can you defend those people?”

“For the money.”

“But, seriously, you could make far more in some other specialty.”

“Sure. But I crave the excitement.”

“How can you defend a guilty person?”

“You mean a kid possessing marijuana? . . . Or a housewife who shoplifts?”

“No, no. I mean a murderer. How can you do it?”

“Well, I could tell you that I defend the constitutional rights of the individual against the power of the state.”

“Sure you could.”

“Well, you’re a doctor, right? If a patient is sick or injured you don’t ask if he is a bad person before you treat him.”

“If he can pay or has insurance.”

“And you do your best, don’t you? Well, isn’t the highest calling of a doctor to treat the most seriously ill patient? The greater the risk to life the greater the skill required ... the greater the challenge . . . And the greater the satisfaction when you do your job right.”

These answers sufficed in the 1960's when I began. Those of my generation, after all, had been raised with the same myths about heroes and anti-heroes. And it was the era when challenging The Establishment was considered . . . Cool.

But in the 70's, while I maintained these values, others of my generation began to drift. The horrors inflicted by such as the Manson family changed attitudes about the death penalty. The feminist revolution raised consciousness about sexism in the legal system. Talk of high crime rates and judges soft on crime permeated the culture. The Warren court yielded to the Burger court, then the Renquist court. . . .

Women I knew asked: “How can you defend — rapists? Pimps? Child molesters?”

They pushed changes in the law to make it easier to obtain convictions: eliminating cautionary instructions, the need for corroboration, any inquiry into the “victim’s” mental state; admitting the accused’s priors. All the while, lengthening sentences, the dire consequences of convictions.

I tried to remind them of my old heroes like “Atticus Finch” who represented a black man accused of raping a white woman. In the ardor of the feminist enlightenment, a fact was forgotten: Laws that make it easier to convict while increasing punishments are risky. They increase the chances of convicting innocent people.

It has taken heroic work by such as the lawyers and volunteer law students of the Innocence Project to use DNA testing to expose the numbers of false convictions for rapes that resulted from these laws.

In the 80's, the nasty questions were expanded as society became less tolerant of wrongdoing:

“How can you defend . . . Crack dealers? ... Drunk Drivers?”

And then — up to now: “Street gangsters? Bullies? Cigarette smokers?”

When my erstwhile “radical” friends faded to “liberal” then to “moderate” and eventually “conservative” and / or “libertarian,” I had to construct a better argument.

“Hey, I am the only true conservative / libertarian here. I fight for the individual against the greatest exercise of power a state can exert: imprisoning or executing him or her. Remember, Barry Goldwater said: 'Extremism in the defense of liberty is a virtue!'"

Eventually, I felt that I was the last person to believe the classic dictum: “It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.”

Many, including the members of the appellate courts now write that no one is promised a “perfect trial” and that notions like “harmless error” and “finality” and “speedy justice” demand affirming convictions despite deficient evidence.

These judges apparently agree with those who would turn Blackstone on his head: it is better to convict ten people on less than convincing evidence than to allow one suspected child molester or potentially dangerous serial murderer loose.

In my bitter moments, I have been tempted to respond to the nasty questions like this:

“How do you feel when you get a child molester off?”

“Great! They are well-known recidivists. So they are likely to do it again and I can defend them again and again. And make more and more money!”

(Thereby eliciting the satisfying open mouthed gape — as the response from the audience in Mel Brooks’ “The Producers”).

THE CLIENT AS ADVERSARY

Once having dealt with loved ones and social acquaintances, the lingering source of our stress is always going to be our clients.

I often think that a basic flaw in our system is the “promotion” of criminal lawyers to other work. When a public defender is made a supervisor in that office or any defense lawyer is named to the bench, there is bound to be trouble. You have taken away from the person trained to be an advocate the principal cause of his aggravation — his clients.

Now, the supervisor sees his adversaries, the main sources of his worry, as the lawyers he supervises. Naturally he resents them and blames them for his stress and making his job harder. Same with the judge. He no longer has any clients and must get back at those who appear before him. He knows every lie and trick they may try in order to avoid responsibility for their conduct and he is ready for them.***

[***The D.A. who becomes a judge is in a slightly different position: he still perceives that he is serving his “clients,” “The People”. He continues to be a tool of law enforcement.]

The most frequent stories told by defense lawyers to amuse their colleagues or others are about the foolish things their clients have done to foul up their cases. As examples, below is a list of things my clients have done. Every defense lawyer can claim similar events.

They drop the dope on the street right in front of the oncoming marked police car. (“That’s not possession, is it, if I throw it away?”) They leave the rest of the dope in the seat of the police car after they are removed. They waive their rights and sign a confession, admit to their homies over tapped phones, then adamantly deny all to their lawyers. (This often stems from a belief that a lawyer who you confess to will not “fight for you.”)

They will insist on an impossible defense (such as alibi) when a perfectly reasonable one which conforms to the evidence is available. If you work out a wonderful disposition, they will turn it down even though it assures the maximum punishment. They will insist on testifying when it is clear that they will make a terrible witness and that relying on the lack of proof gives a better chance.

After you have striven to suppress evidence of prior convictions for possession, they will testify: “Not only were these drugs not mine, but I have never seen drugs before.” Thereby causing a smiling judge to now permit impeachment by those priors. When they are convicted they will demand their file and try to appeal based on your “incompetence”.

Stories about fumbled commission of crimes are common. Just one from my past: My client enters a fast food store, orders a burger, removes a $20 bill from his wallet. The cashier opens the register. My client draws his weapon, demands the money from the till, leaves . . . and leaves his wallet on the counter. Twenty minutes later he sees a police vehicle outside the store. He enters, “I want to report a stolen wallet.” The officer holds it, views the photo I.D. matching, the cashier confirms “That’s him.” The client tells me, “It must have been someone who looked like me who stole my wallet.”

"STUPID IS ... OR IS IT?" The tempting answer is that people like this are merely . . . Stupid.

Certainly, I have found that I.Q. testing and records have sometimes shown clients to be under-achievers in school often with problems of ADHD or other cognitive defects that affect behavior.

But stupidity does not answer the question. It is too vague, too convenient. And furthermore, it doesn’t account for the smart people who do stupid things.

I put together this six pack of Unusual Suspects to illustrate the problem.

Number 1, 3, 4, and 6 are famous men who were thought of as the smartest in their field. Top of their classes at prestigious universities. Policy wonks. Numbers 3 and 6 were deemed to possess encyclopedic wisdom. Number 4 was known for his discipline and judgment on the course.

[I will explain #5 below, and #2 at the end of my essay.]

Each not only transgressed, but did so in a manner that seems in retrospect to be blatant and arrogant. Smart people like these should have anticipated they would be exposed considering their positions and the huge stakes at risk. (I might have added former governor Mark Sanford or any number of other politicians, athletes and celebrities who have fallen from grace in a similar scandal).

One explanation for the frequency of this kind of conduct was offered by Dr. Frank Farley, former president of the American Psychiatric Association, who labeled them as “Type T Personalities.”

The “T” stands for thrill seeker . . . the kind of person who chooses a risky career, apart from an ordinary life. He thrives on uncertainty, novelty. He becomes addicted to passion, craves the “drama” of the big stage with its attendant high wire act. He experiences life to the fullest: the rush of chemicals: Adrenaline . . . testosterone . . . dopamine — similar to intoxication and sexual desire. Dr. Fahey concludes: “You know what kind of decisions you make when you are intoxicated.”

Doesn’t that sort of describe our clients . . . To a “T”?

Oh, and just in case you thought this is limited to males, there are many examples of females who have fallen because of similar conduct.

Mary Kay Schmitz Letourneau is one notorious example. The daughter of Orange County congressman and John Bircher, John Schmitz, who was later revealed to have fathered two children during an extramarital affair.

Mary Kay was married with children when she fell for one of her students, a precocious 12 year old boy. She was prosecuted when she became pregnant with his child and violated terms of her parole by continuing to see him, was imprisoned and later married him.

Ruth Snyder is another. Her story inspired the writing of “Double Indemnity.” In the 1920's she was a bored suburban housewife whose husband never got over the death of his high school crush, who died before he could marry her. Insensitively, Mr. Snyder never tired of reminding Ruth of his melancholy throughout their marriage and she was fed up. One day the doorbell rang and a handsome salesman entered. An affair ensued and the lovers conspired to kill Mr. Snyder after Ruth had secured his name on an insurance policy that paid double for violent death.

One night she reported that an intruder had knocked her out and strangled her husband, stolen jewelry. It took police only a few hours to solve the crime: Ruth and her boyfriend had failed to show evidence of forced entry, had made Ruth’s injuries unconvincingly severe, and had left the supposedly stolen jewels under the mattress. Ruth confessed that night, blaming it on the boyfriend, who was caught, blamed it on her. They both fried in Sing Sing’s chair.

[The famous picture of Ruth Snyder a moment after the switch was thrown was snapped from a camera hidden in the pants leg of a reporter.]

[The famous picture of Ruth Snyder a moment after the switch was thrown was snapped from a camera hidden in the pants leg of a reporter.]So to the volatile soup of power and sex, add greed as another impulse for taking foolish risks.

AKRASIA In our 6 Pack, #5 is Alan Greenspan. He is apparently happily married to newswoman Andrea Mitchell. But he is notable because, as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, he was a respected expert on the financial world, often a reasonable voice urging caution in economic policies. Yet, he utterly failed to anticipate the meltdown of markets in 2008 due to the disastrous risks taken by established banks and other conservative institutions. Afterward, he evinced head scratching embarrassed puzzlement that the logical inherent restraints of the free market did not cause institutions to act in their best interests in protecting their investors and consumers.

Greenspan had been an influential proponent of de-regulation, arguing that operators in the free market would be internally checked by the need to act reasonably in its own best interests.

What Greenspan failed to consider was the temptation of greed, the emotions overwhelming “conservative” values of caution.

There is a recognized description of this human behavior. AKRASIA, which is defined as the state of acting against one’s better judgment.

Plato in his writing, describes Socrates as being appalled at the notion that people might act in such a way: “No one goes willingly toward the bad.” ... A person, according to Socrates, never chooses to act poorly or against his better judgment; actions that go against what is best are only a product of being ignorant of facts or knowledge of what is best or good.

Later observers (philosophers, theologians, psychologists) have disagreed and the consensus is now that the phenomenon is so common as to be normal. Suggested reasons delve into the reasoning process, how the mind makes the choices between logic and emotion, the evaluation of comparative goals, and moral valuation.

The traits which most define our client’s behavior include:

1. Impulsiveness

2. Poor risk assessment

3. Self-destructive ideation and behavior

4. Selfishness and inconsiderateness of others

5. Denial of responsibility for actions; shifting blame to others or society

6. Denial of obvious facts

7. Perception of self as victim of unfairness

8. Mood swings, emotional instability, rage, depression, etc.

9. Reliance on peers in making choices

10. Testing limits of authority

11. Experiments with substances for self-medication

These are the exact traits that define adolescence. It is not unexpected that statistics prove that the years in which people commit the most crimes are between age 16 and 29.

It is apparent that our clients are acting out in the manner of teenagers.

Recent scientific breakthroughs have pinpointed a possible cause of such behavior in physiological findings.

Dr. Jay Giedd of National Institute of Mental Health is one among a group of medical experts who have been experimenting with the brains of adolescents through use of Functional MRI’s.

These experiments suggest that although the adolescent brain is fully developed in size, it is far from mature. The cause seems to be in the neural “wiring” that continues to develop in complexity past adolescence far into adulthood. The wiring is needed for the brain to fully perceive threats, to acquire complete knowledge of facts in order to make reasoned judgments.

The deficiency is particularly apparent during times of stress (such and when our clients must decide whether to respond violently to any situation: fight or flight). And the adolescent is hard wired to be influenced by his peers, even their mere presence, when he has to make decisions. He is more likely to act rashly, aggressively, seeking the approval of his peers and wishing to impress them.

Unfortunately for our profession, this study may be dangerous. The implication that our clients cannot alter their behavior because they are hard wired to misbehave violently might be construed as defining psychopaths or sociopaths, impervious to rehabilitation, undeterrable by threats of punishment.

However, it does suggest that the passage of some time, enough for the brain to mature, will alleviate the risk of future criminality among young adults. Thus, the lengthy imprisonment of young offenders is not needed. They will cease to be a threat sooner than previously thought.****

****[This trend of evidence led to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that life without parole was cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the 8th Amendment when applied to juveniles.]

RISKY BUSINESS In a real sense, risky behavior is not exclusive to our clients, although it is a hallmark of their personalities.

We have all transgressed. Throughout our lives. As toddlers, we test our parents patience by misbehavior. We act contrary to their warnings. Stay up late. Violate the rules. Get punished and do it again. Get away with it time after time.

In school, we don’t do our homework, cheat on an exam, cut a class, smoke a joint in the bathroom. Feel the rush of fear of being caught. Being called on in class while unprepared.

When you drive on the freeway. In your mirror you see the blue and red bar, the CHP cruiser! You look down, you are going 80! You take your foot from the pedal, tap the brake, slow. The cruiser speeds up . . . passes you, does for the red sports car doing 90.

You monitor your heart rate. The adrenaline, the dry mouth. That was the rush of adrenaline, dopamine, testosterone. The dizziness, the rush.

Did you then avoid that feeling? ... Or did you crave it? Was it frightening? Or exciting?

Always following the rules is boring. We need drama in our lives, either vicariously, through our entertainments: sports, video games, role playing fantasies, films . . . Or in our lives.

Possessing a weapon is thrilling . . . The weight of it, the coldness of the steel, the shape of the handle. The sense that it is dangerous. So easy to pull the trigger and . . .

Risk taking is not only normal. It can be a good thing.

We all take risks in our lives. It is what we do when we take our first steps, ride a two wheeler, take our first swing at a baseball, ask a girl for a date, fall in love, give ourselves emotionally to a mate, decide to have a child, or choose a career with the responsibility for another’s life in our hands.

There are those who act impulsively in making these choices. They usually wind up in divorce courts, bankruptcy courts, dependency courts, rather than criminal courts.

If they avoid courts, they may not avoid the therapist’s couch, sometimes over and over again.

They do other things our clients do. They abuse medications, themselves, or others.

“Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.”

Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience and Other Essays

And that brings us back to our 6 pack. Number 2 is my current client. He is accused of committing 10 robberies of small stores. In the first few, the culprit wore a ski mask and gloves, showed the gun, took the money, zip, less than three minutes. Captured on video but not very helpful.

Then in one of them, his partner was delayed, taking candy from the displays before leaving. So he goes back into the store — after removing his mask from the lower part of his face exposing a distinctive goatee. The video image helps

police make an ID. In the next few robberies, he doesn’t bother to wear a mask or gloves, his hairline, goatee uncovered. He touches items, leaves latent prints. In another he spits on the floor, leaving DNA.

Some of the incidents are weaker than others, guilt depending on the inference that the same person committed all of them. But the M.O. is not so distinctive. In fact, other similar crimes by attributed to other suspects have occurred around the same time to similar and in some cases the same stores.

Realistically, his best chance is to admit one or two of the charges and deny the others, thereby limiting his exposure.

But no, my client insists on an alibi defense, claiming to have been in Mexico, coincidentally, from the date of the first crime until the date of the last crime.

So I should not be worried. Right?

As an addendum to this post, I must add another confession, which is pertinent to the subject.

The elderly gentleman shown here is my mother's father, my Papa Hymie. The chubby kid is me, @ 3 or 4, I would guess, on the beach at Coney Island.

I remember Papa Hymie as a dignified grandfatherly presence throughout my childhood and my siblings and all other relatives treasure his memory as well. He was born in 1886 in Kiev and came here as teen, I believe. I used to love to listen to his stories about seeing prize fights with Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey. He liked sports, especially "the ponies". He used to joke that the horses he followed followed other horses.

Recently I researched family members online and found this:

It may be hard to read. It is a copy of a page in the New York Sun in 1934. The story on column one relates crime news, including an arrest of Herman Boriskin for involvement in a confidence scam involving the "policy racket" which was a common gambling scheme (an illegal lottery) among tenement dwellers in the Great Depression, especially recent immigrants who dreamed of hitting it big.

The reason I am including this is that it suggests to me that I should not be overly judgmental about our clients. They are really not all that far from our lives after all.