While in Bangkok, our companions on a tour of the Floating Market had been a Canadian doctor, his wife and two children. When we remarked to them how drab, grey and poor the streets and Klongs of Bangkok seemed to us, they exclaimed that to them it seemed quite prosperous after India from where they had just come.

After only a 1/2 hour ride in from the Calcutta airport I understand and agree with everything they said. The airport is modern and relatively efficient. But soon we are riding in a ramshackle taxi down a dusty highway, past fields, a river, cows and water buffaloes.

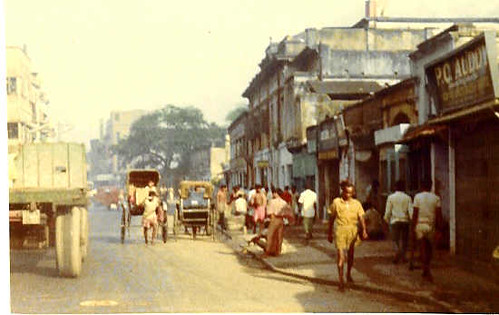

As we approach the city, the people begin to be more numerous and soon the streets— including every inch of sidewalks and gutters— are filled with hundreds of thin, often emaciated faces, horsecarts, bicycles, a few smoky cars, and occasional rickshaws carrying fat and thus apparently rich women in colorful saris.

A bus goes by, more rickety and spewing more black smoke than any in Bangkok, tilting with people hanging to its sides like those to a lifeboat. There is a streetcar jammed to the gunnels. And of course, the people of whom we have read and prepared ourselves for; they unimaginatively poor, who live and die in the street by the hundreds of thousands. There they are on every block, in the precious shade under the overhangs of decaying buildings. Children lay limp on mothers’ robes, old men stare blankly. Men dodge traffic fatalistically and no one smiles.

I choke down the feeling of guilt as we ride by like Maharajas in our junky taxi. I’ve promised myself I would not feel this way, but here it is, overwhelming me.

Our taxi goes down a main thoroughfare where there were government buildings, hotels, and a large park (The Maidan). Honking his horn all the way, our driver turns into a side street which is a narrower version of the many poor ones we’ve passed. A way up we see the Lytton Hotel, which our guide book states is next door to our destination.

Our driver slows, and points. The sign tacked onto the wall says:

“FAIRLAWN HOTEL — >”

I’m thinking that we’ll have to get out and drag our bags the rest of the way, through the gauntlet of people who I can see are drying their palms for outstretching. But, no, he turns into a driveway.

“It certainly does have a pretty garden,” Bijou says, referring to the hotel’s description in our trusty guidebook. And it is calming to the eyes after what we have coursed through in the past half hour.

We get out. A porter snatches our bags. It begins to rain. It’s been sunny and white hot on the drive in. I had noticed tumultuous thunderheads at the airport. I’d also seen puddles near the runway as we taxied. As it has all during our travels in Asia during the rainy season, I fully expect a downpour. And here it is, a steamy, violent outburst.

We sign the register and follow the porter. Near the desk, in the garden of green plants and palms are chairs around white metal painted tables with umbrellas. On the other side is a dining room with tablecloths neatly spread and big fans overhead. We climb a marble, carpeted staircase and walk through what we would call a lounge. I suppose the English would call it a salon or parlour. There are black lacquered cases with knick-knacks: china dolls, plates, Buddhas, other statues. Four padded rattan chairs surround a round glass topped table. To the right is a veranda, sun-drenched, with more chairs, tables and brass pieces. I’m looking for Somerset Maugham with a gin sling.

We walk to the left and are in a large marble floored room. Large black statues in wood stand near more display cases. Punkah fans droop from the high ceiling. We walk by a large desk which stands at the far end of the room. A man sits behind the desk like a librarian. We cross a short stretch in the rain and are at the door to our room which fronts on a motel-like exterior walkway.

The porter opens the door.

“No air conditioning,” I blurt in a panic, noticing the ceiling fan turning slowly. But as soon as I say it, I see the machine set into the window.

The room is larger than most of those we have had on the trip. Two single beds face the door on either side of the room. Between them is a red and black painted table and two smaller ones on either side of it. Two upholstered chairs face the tables, their backs to the door. The windows back each bed, curtained neatly. There is no view, the windows are locked. There are wardrobes painted a dull yellow as are the walls.

The porters (another had walked alongside the one who bore our luggage) wait. I give the one who had carried the luggage two rupee notes. He looks at his palm, scratches the crisp bills together and eyes me impatiently. I thank him and turn away. He walks to the door, mutters something to his mate, shows his palm to prove the point, and stalks out.

“Myra says to give the porter one per bag,” Bijou says.

“I did, but you saw his look.”

“The hell with him.” Bijou is as as angry and tired as I am with the hustling we have endured so often in Asia.

“Smell!”

I did as Bijou instructed and was met by the strong odor of turpentine.

“Well, in Hong Kong we complained that the paint was peeling off the walls. Now we’ve got fresh paint.”

We sniff about the room. A writing desk stands next to the door. On the other side is a curtain and through it the bathroom; barely western. An old chipped porcelain tub over which hangs a pipe connected to a painted shower head. A sink in the corner. As if to cater to the expected tender tummies of its users, the john sits right next to the doorway. Its wooden seat is painted putrid green. A pull chain hangs like a hanging rope from a gallows. All the fixtures are like the atmosphere of the entire hotel — as if preserved from a distant age.

We sit on the bed and look about cautiously. Slowly we go through the mental process of acclimatization that has now become a familiar pattern in our travels. The drive in from the airport had been, to say the least, breathtaking. We had often grasped each other’s hand in the way a child comes back and hugs its mother from time to time. More than once, our eyes turned from the “sights” toward one another; our eyes met, and rolled to indicate “Wow!” or “Oy vey!”

Now we look at each other from across our new home. Bijou says: “The hotel is fabulous.”

I say: “Let’s rest and wait for the rain to stop. Then we can walk around the place a bit.”

“Okay,” she agrees, “then let’s walk to American Express and collect any mail.”

The plan and the prospects of word from home cheer us.

We retrace our steps, through the lounges which are cheerful and amusing, and go downstairs. We get a map and I walk over to a man who is poring over the register book. I ask him for directions. He is a spare, dark little man, with black wavy hair sprinkled gray, and a Ronald Coleman mustache. He wears a white shirt, sleeves rolled to the elbows and a handkerchief knotted around his neck. His eyes sparkle amiably. He speaks English in an attractive, clipped Indian accent. He shows us on the map where we are in relation to the monuments, restaurants, etc.

I introduce Bijou and myself.

He says: “I am Ali Baba, the Muslim.”

Okay.

We walk through the garden and driveway and turn at the wall which fronts the street. As we reach it, a shine boy pesters me, a taxi driver hoots his horn and beckons. A young boys begs, sad faced and empty palmed, walks apace with us, not threateningly—at least not intending to threaten, at least not yet. Soon, he is joined by other boys, who match my increasingly rapid New York-bred walking pace, a few steps behind, palms upraised, offering help for rupees.

The temperature must be over 100, and the air is sluggish. We walk in what seems the right direction, though I could not be sure, still unfamiliar with the map. As we trod the cracked pavement, threading between puddles, we pass people in rags sleeping on the sidewalk.

Our companions who continue their insistent pleas are joined by a young man who gets in step with me and asks confidentially, “You want anything, anything for the lady? Change money, student card? Buy anything?”

My answer to all offers is a head shake, then a “No, I’m sorry,” then “No thanks,” then “No!” Nothing fazes them: ignoring them seems the only way but it is like ignoring a swarm of bees around your head.

For once, Bijou does not complain of my rapid pace. She grips my arm tightly and breathlessly keeps up. We both want to run and hide.

We turn up a main street, through crowds. There are shops, each keeper beckoning — vendors of books, toys, fruit, nuts — all arrayed on the wide sidewalk. And massive Brahma cows just sitting on the sidewalk. People walk around the beasts as though they are pieces of furniture in a living room. And always the eyes and palms often alongside us for a block or more, seeming interminable and to us, unbearable in their insistent reminder of our relative wealth.

The buildings are in varying states of disrepair. All look old, none of the granite, steel and glass of modern cities. Paint is tired looking, chipped and faded and grimy. Here and there underlying bricks show through cracks in plaster facades.

The street is hectic; trams, busses, taxis, people rushing every way, threading recklessly across the jammed street. Here and there cows stand on curbs and in the traffic lanes, like stalled cars and are treated similarly.

We walk almost silently, speaking only to each other about whether we are going in the right direction, or to say “Ignore him,” or “Don’t look” at some particularly heart-wrenching specter. But constantly, to the pleas and nagging, we spout ever more insistent and less polite “No’s.”

Finally we enter the Am Ex office. It is blessedly air conditioned. We take stock of ourselves. Bijou’s face is sunburn red; she looked near to fainting.

“I’ve never sweated so much,” she says.

I can see the beads on her forehead. I am concerned; Bijou is pigment deprived, her skin defenseless against the searing sun. Her complexion registers heat like a cheap thermometer — pink to red to magenta, then steam. She never sweats in L.A. I give her my handkerchief.

My darker skin sweats with far less provocation. Now, my dashiki hangs from my shoulders, filled with water and heavy. Sweat pours from under my hair, down my neck, my back, into my shorts, down each leg and into my socks.

We catch our breaths and light cigarettes. We’re directed to a desk and we ask for mail. A stack is brought out and gone through one by one. Nothing. Bea’s shoulders slump. I try to look sympathetic.

“The mails here are probably slow.”

But we’re both dejected, not only from the disappointment usual in such situations, but also because we feel we have gone through so much to get there, driving ourselves through terrors with the goal of getting a word from home.

After the cigarettes, we’re ready to run the gauntlet again. I crack that it’s a good thing we both have good strong Polish peasant blood — we just plod on, pulling our plows behind us.

When we return to the hotel, we are greeted by a smallish European woman who stands behind the front desk. She asks us our first impressions of the city. She speaks with a distinct English accent. She can tell more from our excitement, exhaustion and sweat than our words: “Incredible” and “Overwhelming.”

“Yes,” she says. “Calcutta has that effect. We once had an Englishwoman from New Zealand. You know, we used to get the Sundowners and such. She checked in, went out for a walk and returned after just a few minutes. Fainted dead away. Spent the rest of her stay in her room. Really, she wouldn’t leave her room!”

She begins a prepared speech. “I’m Mrs. Smith, the proprietress. I hope you’ll enjoy your stay here. The place has been in my family for forty years. Father was a major in the army. He bought it. Used to be called Canada House.”

“I’m dying for a drink,” Bijou says.

“Of course. Try some Limca. It’s quite nice. Refreshing.” She calls a crisp order in Hindi. In a moment, bottles of a cloudy soft drink with straws are set on a table near us. It is cold and refreshing, not as sweet as Coke, lime-flavored.

Mrs. Smith wears an absurd jet black wig styled in a flip. Her moon shaped face is a little too made up for the scene. Her cylindrical torso is wrapped in a sheath dress. Of course, she wears spiked heels. The effect is a bit unsettling. She doesn’t look like a proprietress of a charming, eccentric hotel in the middle of Calcutta, more like a Jewish lady from Miami Beach on her way to a Bar Mitzvah. [Years later, I compare her to Mrs Fawlty of Fawlty Towers.]

“I think you’ll like the food. We have full board, meals, morning and afternoon tea. I’m sorry you missed breakfast, but lunch is at one. Many of the servants have been with us for 40 years; our chef is quite good; he’s been with us a long time.”

We tell her we think the hotel is lovely.

“I’ve collected all the little things myself from all parts of the world,” she says proudly. “I’ve been everywhere, you know. Where have you been?”

We tell her about Japan, Hong Kong and Bangkok, and of our plans.

“Charming! Hong Kong is lovely. My daughter is there. Not what it once was, but not as bad as this place.” She nods her ample chins in the general direction of India. “Gone to hell in twenty years.” Then remembering her place in the tourist business: “It is fascinating, though, isn’t it. We’ve got very friendly guests. From all over the world. Couple of Americans, too.”

In a lull, we excuse ourselves. Bijou says: “So long.”

“Yes, so long,” Mrs. Smith laughs, apparently easily amused. “See you later, alligator,” she intones in mock-American.

“After ‘while, crocodile,” Bijou tosses back.

“What? After while, crocodile. Ha-ha. That’s jolly good. Yes, I must remember that.”

After showering and relaxation, we anxiously and hungrily pad through the lounges to the dining room. We’ve read that the fare is western food and speaking to Mrs. Smith, expect boiled beef and Yorkshire pudding. We’re placed at our table by a waiter dressed in Indian whites. Another wearing a red turban pours ice water into our glasses. The table is formally set with linen. A third waiter brings a tray of food to Bijou, then to me.

There are fried egg roll type things and boiled potatoes. Since I am famished and have not seen a potato for three weeks, I heap my plate with as much as seems decent. The potatoes are marvelous and the egg rolls turn out to be just that: an egg paste lightly spiced, and quite good.

We’re afraid to drink the water, so order Limca and drink them quickly. We’re quite satisfied, no longer famished.

A servant removes our plates and replaces them with another. The red turban waiter, who I now notice is badly cross-eyed, stands by Bijou with another tray. This one contains a large dish of rice, another of red vegetables, and a boat of curry.

“Not too hot?” Bijou asks timidly.

“No.”

I fill my plate. A servant with yet another tray arrives, with bowls of a variety of chutneys: mint, potato, onion and pepper. We sample each. We’re greatly impressed: two courses, one western and very tasty; the second Indian and non-threatening. We find our appetites renewed.

We also find that in its insidious way, the curry begins to bite. Like Mexican chili, it burns the lips, tongue and palate, makes the eyes water and in a particularly strong dose, clears the sinuses. But unlike Mexican food, the Indian curry continues to singe all the way down. And after the initial fire, comes the afterburner, way down like a slug of Uzo or Slivovitz thrown down your throat into the pit of your stomach.

We quickly sip the last of our soft drink and look longingly at our cold glasses of water. Other diners are guzzling their water, the servants at their elbows with chilled pitchers. But we don’t dare. It is our first day in India; too soon to be sick. Soon, a bowl of grapefruit type thing appears before us and we suck those dry.

Feeling renewed, we decide to brave the horror of the streets again. We strike off in the opposite direction, toward a shopping area called the “New Market.” Bijou is desperately in need of a sun hat. On the way, we witness again the “realities of life in Calcutta,” which, even as we view them and try at times to avoid viewing them, seem unbelievable. Again, the beggars, the taggers-along, the hustlers.

I clutch Bijou’s oversize carry-all and Bijou clutches me. After a few blocks that seem to take years, we reach the New Market. It is a block long brick building fronting on a wide pot-holed street. We cross the street and enter a maze of shops and walkways. Shops selling clothes, foul and sweet smelling food, toys, books, fabrics.

But no hats.

As we walk aimlessly the shopkeepers in entrances beckon us insistently.

Of course, we are never alone. Our guidebook, in its authoress’ lady-like way, describes the “Pengalis” as boys who are not beggars, but people who make their pitifully meager livelihood running errands, carrying packages or guiding tourists. At night, they sleep in the streets. Her description is an annoying understatement. These men who might have once been boys nag and pursue us from the moment we cross the street. Many carry wicker baskets. “Carry your things, sir?” “Want to buy something?” “Something for the lady?” “Some silk?” “A dress?” On and on, the voices.

“We only want to buy a hat to wear, not to carry.” “We are sorry, but we do not need anyone to help.”

It is no use. The chorus continues. I’m polite. I’m firm. I’m insistent. I’m rude. I’m angry. “No.” Again and again.

Bijou verges on tears or flight.

I angle us into a book shop and we try to browse. The proprietor is at our side in a moment.

“You want a book? We have many kinds. What would you like?”

I say we’re just looking and I try to read the titles of the worn covers.

He hovers; there is no fun in it.

We leave by another doorway around the corner. We’re met by new faces with baskets and voices.

“We are only looking, not buying.” “Please, no thanks.”

Others take up the pursuit as we continue.

“Please leave us alone.” Bijou has stopped, and pleads, her voice near panic.

I try calm reason. “Please, my wife is not well. You are bothering her. Please go away.”

Still, the voices.

At last, we see some hats in a window and duck into the store. We bargain with an insistent old man and make the sale. Bijou wears the hat as we leave.

The droning begins again. We search for a way out. We are in a maze and it seems like the nightmare might go on forever. But we see a light and soon are in the street.

We find our way back to the oasis of our hotel, again through the gauntlet of decaying misery and pleading voices. We rush through the gate and fall into wicker chairs, exhausted and soaked again to the skin.

We are just in time for tea.

In the evening, after another ample and varied meal, we meet some of the other guests. One is a blond haired guy in his mid twenties. He’s been raised in Kentucky and has a mild drawl. He’s worked on fishing boats in California, Canada and Alaska and worked his way over here on a merchant ship. He’s been to Bombay and come east to Calcutta about six days ago.

“Blew my mind.” He’s been sick. Tonight’s is the first meal he’s been able to digest in a few days. He chuckles when he talks about it and doesn’t seem too troubled by the experience.

“Went to a store and bought some of this,” he says. He takes two bottles from a newspaper wrapping. “This one’s paregoric, made of opium. Can’t get it in the States, even with a prescription,” he laughs. “Here you can get anything. A guy in the street offered me a jar of cocaine yesterday. The other one is ampicillin.”

He shrugs. “I just walked in an plopped down the rupees. A slug of paregoric settled my stomach — a bit too much will really set you straight!”

Bijou asks him how he knew where to go.

He chuckles. “My guide, a little guy who hangs around here. He’s been showin’ me around. Knows the city real good. I give him a couple of rupees a day. All he wants is my jeans when I leave.” He pats the thighs of jeans that are perfectly faded, streaked, and worn.

Bijou notes what a prize they are.

“Yeah, I love ‘em. I think I’ll give ‘em to him,” he says kindly.

He’s leaving for Kathmandu the next day, he hopes, by train. It will take 24 hours and he has to bribe the guy at the station. The plane flight we’ve booked for the next week takes an hour and a half.

“Then to California,” he says. “I have a boat hull in Seattle. If I can get a ship back I can start putting some money together and build it. Then I’m gonna get a crew and sail the islands of the Pacific. I’ve been through some of ‘em.” He rattles off some exotic names. “But there’s thousands. Nobody goes there. I know a guy who does it all the time. He gets girls to pay to be the crew.”

He laces his hands behind his head. “I been traveling for 10 years and I could do it forever. No sweat. I love it.”