"Pittsburgh - A T-ball coach allegedly paid one of his players $25 to hurt an 8 year-old mentally disabled teammate so he wouldn't have to put the boy in the game, police said Friday.Memo to secretary: if this guy calls to hire me to defend him, I'll be on vacation.

... The boy was hit on the head and the groin with a baseball just before the game, and did not play... 'The coach was very competitive,' [an officer] said. 'He wanted to win.'"

Saturday, July 16, 2005

Adventures In Crime / T-Ball Hitman

The human capacity to find new modes of criminality always thrills me. This from L.A. Times, July 16, 2005, p. A-8:

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

Journal / Letter to home / 14 November '74

14 November Luxor

Dear Ron and Laura,

I give you warning that this letter is likely to ramble quite a bit, tending to sound dreamy and disconnected. The explanation is that my mind right now is exactly that way. It is now 7:30 a.m. and we are in our comfortable, though pleasantly seedy hotel room in Luxor, the site of ancient Thebes which is in Upper Egypt—which is really South of Cairo and ancient Memphis, the sites of Lower Egypt. I told you this would be disconnected and about as rational as anything else here.

..I am obtaining an education I never received: in art, architecture, history, religion, politics, philosophy.

We have stood in the place where The Buddha stood; walked the path Christ walked to the Cross; touched the rock upon which Abraham is said to have been ordered by God to sacrifice Isaac and from which Mohamed is said to have risen to heaven.

We’ve stood on the hill where Orestes was tried and acquitted for matricide and Socrates drank his hemlock and where St. Paul preached his first sermon to the Athenians.

We’ve stood on the stage of the theater where the Greek tragedies were first performed. I have hiked in the hills to seek the birthplace of Theseus.

I’ve run the track in the stadium at Olympia and we've driven through the Pass of Thermopylae and the crossroads where Oedipus gouged his eyes out in despair.

We’ve sought guidance from the Oracle in Delphi.

We‘ve seen the hair of Mohamed, the skull of John the Baptist, touched the “tomb” of Christ.

Somehow, doing all that gives me a thrill of vicarious participation in history and, if not a grasp, at least a “feel” for what the events must have been like.

In the Egypt Museum we viewed the mummies of Rameses and other pharaohs, their gaunt blackened skin and dusty hair still on their skulls., puny and human, telling more truth than the giant monuments they dedicated to their glory, the pyramids and colossal statues, pretentions to Godliness.

Yet standing under the pyramids or riding past them as we did on swaying camels, I could sense some of the awe people over the ages have felt in these achievements.

One can be cynical about many of the ancient monuments and much of its art from a modern perspective. Almost all the “wonders” were built by slaves, ordered by the few incredibly wealthy while the many suffered unrecorded deprivation. The Art was created mostly to promote belief and worship of deities and rulers and therefore to encourage the superstition and subjugation of the masses.

One can also be callous to the structures themselves: next to New York’s skyscrapers, the pyramids are mere bungalows. The Temples to Apollo or Amun-Ra, the sun-gods of Greek and Egyptian, seem silly next to our conquest of the moon.

I have heard other tourists speaking in very blasé terms while looking at the Taj Mahal or Parthenon. I have expressed the cynicism myself in my moments of reflective depression.

You cannot avoid feeling the ironic paradox of the remnants of glorious civilizations amidst the squalor of the present; or viewing the striving for perfection and rationality of the Ancient Greeks while also experiencing the crudeness of contemporary people.

But there is more. Ancient Egypt was one of the earliest attempts to grope for something civilized. Not long before in Man’s history was the stone age—prehistoric Man little more than animal. But something stirred his mind, his imagination, daring that he could try to solve the riddles of the universe.

Reading all that over, I see that I have expressed it very poorly; it sounds like a lot of pretentious drivel, full of hackneyed phrases and muddled ideas. But it is some distance from my first words uttered when seeing these things: “fantastic” “incredible” or merely “wow.”

Maybe some day I will be able to communicate more interestingly. I am still too close to the experience to express it any other way and my emotions stand in the way of my ideas. I am sure that my “insights” are far from unique—my intellect inadequate to say something new or “important.” All I can say is that it has been a revelation to me and I suppose nothing is known unless you know it yourself.

Of course—and again I doubt that this is an original thought—even if I was totally ignorant of all of history, I would still be its product and participant in its continuum. All the experiences have given me is the awareness of that fact and some tiny inkling of my place in it.

That is only one level of my thoughts on this trip. There are others. There are observations of the ways of life in other places and there is the personal search for my own.

It has been hard to learn how people live in Japan or India or Turkey during our brief visits, as tourists, not speaking the languages, or knowing anybody who lives there. My views must be from scanning the surface, developing an intuition from endless walks on the streets of the cities, talks with merchants and others we contact, riding the ferries, boats, buses, eating in the restaurants, going to the movies.

Other places we have gotten to know better: talking to and living with people who reside there, staying a longer time, seeing more than just the centers of big cities. I feel I got to know Israel and Israelis pretty well—enough to form some judgments—enough to want to come to see Egypt.

Today, at the temples of Karnak, we saw a huge wall filled with bas-relief depictions of (what most scholars believe is) the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and the submission of the Hebrews—the beginning of my heritage?

After a month in Greece, viewing its physical beauty and variety of life styles, from Athens’ city bustle to Metsovon’s peaceful pace to Idra’s careless community of artists, I have come to imagine what it might be like to live there.

But we have a lot more to see and we have only tickled Europe.

There is another—maybe the most important— aspect to this trip: the wondrous development of my relationship with Bijou. Together every moment of every day, coping with one another and the outside world, arguing, looking at things from our individual viewpoints, we have grown together in subtle ways, learned some patience, better consideration of one another.

Despite some trying times of ill temper and occasional sniping that break out into full scale war, we have decided—at least at this point—that we do love each enough, that is completely—and more amazingly, we like and respect each other.

But, as I say, we have eight grueling months to go. ...

Love, Mort & Bijou.

Dear Ron and Laura,

I give you warning that this letter is likely to ramble quite a bit, tending to sound dreamy and disconnected. The explanation is that my mind right now is exactly that way. It is now 7:30 a.m. and we are in our comfortable, though pleasantly seedy hotel room in Luxor, the site of ancient Thebes which is in Upper Egypt—which is really South of Cairo and ancient Memphis, the sites of Lower Egypt. I told you this would be disconnected and about as rational as anything else here.

..I am obtaining an education I never received: in art, architecture, history, religion, politics, philosophy.

We have stood in the place where The Buddha stood; walked the path Christ walked to the Cross; touched the rock upon which Abraham is said to have been ordered by God to sacrifice Isaac and from which Mohamed is said to have risen to heaven.

We’ve stood on the hill where Orestes was tried and acquitted for matricide and Socrates drank his hemlock and where St. Paul preached his first sermon to the Athenians.

We’ve stood on the stage of the theater where the Greek tragedies were first performed. I have hiked in the hills to seek the birthplace of Theseus.

I’ve run the track in the stadium at Olympia and we've driven through the Pass of Thermopylae and the crossroads where Oedipus gouged his eyes out in despair.

We’ve sought guidance from the Oracle in Delphi.

We‘ve seen the hair of Mohamed, the skull of John the Baptist, touched the “tomb” of Christ.

Somehow, doing all that gives me a thrill of vicarious participation in history and, if not a grasp, at least a “feel” for what the events must have been like.

In the Egypt Museum we viewed the mummies of Rameses and other pharaohs, their gaunt blackened skin and dusty hair still on their skulls., puny and human, telling more truth than the giant monuments they dedicated to their glory, the pyramids and colossal statues, pretentions to Godliness.

Yet standing under the pyramids or riding past them as we did on swaying camels, I could sense some of the awe people over the ages have felt in these achievements.

One can be cynical about many of the ancient monuments and much of its art from a modern perspective. Almost all the “wonders” were built by slaves, ordered by the few incredibly wealthy while the many suffered unrecorded deprivation. The Art was created mostly to promote belief and worship of deities and rulers and therefore to encourage the superstition and subjugation of the masses.

One can also be callous to the structures themselves: next to New York’s skyscrapers, the pyramids are mere bungalows. The Temples to Apollo or Amun-Ra, the sun-gods of Greek and Egyptian, seem silly next to our conquest of the moon.

I have heard other tourists speaking in very blasé terms while looking at the Taj Mahal or Parthenon. I have expressed the cynicism myself in my moments of reflective depression.

You cannot avoid feeling the ironic paradox of the remnants of glorious civilizations amidst the squalor of the present; or viewing the striving for perfection and rationality of the Ancient Greeks while also experiencing the crudeness of contemporary people.

But there is more. Ancient Egypt was one of the earliest attempts to grope for something civilized. Not long before in Man’s history was the stone age—prehistoric Man little more than animal. But something stirred his mind, his imagination, daring that he could try to solve the riddles of the universe.

Reading all that over, I see that I have expressed it very poorly; it sounds like a lot of pretentious drivel, full of hackneyed phrases and muddled ideas. But it is some distance from my first words uttered when seeing these things: “fantastic” “incredible” or merely “wow.”

Maybe some day I will be able to communicate more interestingly. I am still too close to the experience to express it any other way and my emotions stand in the way of my ideas. I am sure that my “insights” are far from unique—my intellect inadequate to say something new or “important.” All I can say is that it has been a revelation to me and I suppose nothing is known unless you know it yourself.

Of course—and again I doubt that this is an original thought—even if I was totally ignorant of all of history, I would still be its product and participant in its continuum. All the experiences have given me is the awareness of that fact and some tiny inkling of my place in it.

That is only one level of my thoughts on this trip. There are others. There are observations of the ways of life in other places and there is the personal search for my own.

It has been hard to learn how people live in Japan or India or Turkey during our brief visits, as tourists, not speaking the languages, or knowing anybody who lives there. My views must be from scanning the surface, developing an intuition from endless walks on the streets of the cities, talks with merchants and others we contact, riding the ferries, boats, buses, eating in the restaurants, going to the movies.

Other places we have gotten to know better: talking to and living with people who reside there, staying a longer time, seeing more than just the centers of big cities. I feel I got to know Israel and Israelis pretty well—enough to form some judgments—enough to want to come to see Egypt.

Today, at the temples of Karnak, we saw a huge wall filled with bas-relief depictions of (what most scholars believe is) the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and the submission of the Hebrews—the beginning of my heritage?

After a month in Greece, viewing its physical beauty and variety of life styles, from Athens’ city bustle to Metsovon’s peaceful pace to Idra’s careless community of artists, I have come to imagine what it might be like to live there.

But we have a lot more to see and we have only tickled Europe.

There is another—maybe the most important— aspect to this trip: the wondrous development of my relationship with Bijou. Together every moment of every day, coping with one another and the outside world, arguing, looking at things from our individual viewpoints, we have grown together in subtle ways, learned some patience, better consideration of one another.

Despite some trying times of ill temper and occasional sniping that break out into full scale war, we have decided—at least at this point—that we do love each enough, that is completely—and more amazingly, we like and respect each other.

But, as I say, we have eight grueling months to go. ...

Love, Mort & Bijou.

Friday, July 08, 2005

Journal / Calcutta 24 August 1974

This morning we awoke very early to take a tour of the city. I am letting my mustache and beard grow, poor though that growth is, because I want to look as grubby as possible to cut down on molestation. I won’t shine my shoes or wash my jeans until I leave India.

This morning we awoke very early to take a tour of the city. I am letting my mustache and beard grow, poor though that growth is, because I want to look as grubby as possible to cut down on molestation. I won’t shine my shoes or wash my jeans until I leave India.Bijou, as expected, has trouble with the heat. I do, too, but my skin, so awful in other respects, protects me with its greasiness.

Bijou: “You look swarthy.” Her kind way of saying “oily and ugly.”

She has a bit of the Trots and a congestive cold so is understandably cranky. As our bus bounced around the sweltering streets, she paled and felt faint a few times. The air does not willingly go into the lungs: you must make a conscious effort to breathe.

Our bus wended through sections of slum shanties, the “Bustees,” registered slums. We saw the old section with its government buildings, also in decay, on narrow streets with iron-railed balconies reminiscent of New Orleans. But the tumultuous life in the streets told a greater truth.

Bijou found a way of dealing with beggars. As we stopped at each temple, young children appeared with big sad eyes and little hands outstretched. I have begun to notice that most seem well-fed though clearly poor beyond western imagination. To one such group, Bijou made her blowfish face by pursing her lips, puffing cheeks and widening her eyes. At once, the surprised grins broke out on their faces and they laughed freely in the way only children can. Soon they were begging, not for “pais” but for more laughs. Time and again the trick made them squeal in glee. They called others who joined in the show. They were children after all.

[On that day we went to the Calcutta Zoo to see the rare white tigers. We stood close to the fence surrounding the enclosure and were watching until I became aware that there was a crowd behind us, watching us rather than the tigers.

That alarmed me because I wondered if we were in a forbidden area or something. Then I noticed that they were looking more at Bijou than me. A small boy near her was standing very close and looking up at her. He looked like he might have Down’s Syndrome or some other condition that gave him a very strange manner. When he stared at her arm, I realized why she had attracted all the attention.

Bijou’s hair was very light reddish brown, her skin very pale with brown freckles. She wore a pink scoop neck short sleeve t-shirt like top. It was not exactly revealing by our standards, but compared to the Indian women there who were very dark and wore saris that covered their bodies completely except for a thin band of skin around the midriff, she must have looked quite exotic to the Indians and much more of a rare attraction than the tigers. 20 June 2002]

Tonight we spoke to Andre Amchin, a French seafood merchant in India to buy shrimp and frog legs. He is a large man, a youthful and manly forty, with a full beard and a twinkle in his eyes when he smiles. He is rakishly cynical about India. They are hopeless; in business lazy, in culture and religion un-Christian and foolish.

“They have a temple for rats!” Arms upraised in Gallic shrug, as if that says it all. In cuisine the worst insult: they are un-French.

His conversation is confrontational: America was foolish to destroy Nixon; Watergate was nothing.

He tells us ---rather, tells Bijou in French, who translates --- that Indian women are lousy lovers. “They lie there like death.” Turkish women are better. But the best, of course, i s his French mistress — in Villeparisis (!)

Dr. David Thomas joined us midway through the conversation.

He is in the final week of a 3 month project with World Health Organization of the UN., advising on smallpox prevention. He had previously spent time in India and two years in Lahore.

He is young, grey, serious faced but friendly and possesses a dry wit. He has firm, sound opinions asserted in a doctorly way but without dogmatic certainty.

I ask him what he thought could possibly be done for Calcutta short of blowing it up and starting from scratch.

He describes the small steps that are being taken: water supply, sewage, housing. But he admits that these things are rudimentary and minimal. The chaos is so large, the impediments so many.

He discourses on "the Asian or Indian mind" which rejects planning.

He relates a story. In a rural village, he found rampant vitamin deficiencies causing illnesses long banished from the west: scurvy, rickets, and the like. He left bottles of vitamins, with instructions on dosages. When he returned a month later, he found the villagers had abandoned the vitamins after one day --- they had not been cured by the first day's dose, so they stopped.

He blames the self-satisfied, obstructive bureaucracy for many of the country's ills. They keep statistics of Smallpox outbreaks, but don't follow up with the required innoculations.

All of India is bad, he says, but Calcutta is, by far, the worst; maybe the worst in the world, perilously brinking on hopelessness.

The conversation between the doctor and the Frenchman is hostile. Andre called David a foolish idealist; David calls the Frenchman "a reactionary."

I mediate but I am not impartial. I am annoyed at the authoritarian certainty of the Frenchman. And, I admit, even more annoyed by his attention and outpouring of charm on Bijou. She is vulnerable to Gallic charm no matter how transparent, anxious to use her own.

But he did give us some restaurants in Paris.

Tuesday, July 05, 2005

Journal / Kabul / 10 Sept. to 13 Sept 1974

10 September Tuesday Kabul

I have been very busy last night and this morning, covering great mileage ... between my bed and the toilet. I expected to get sick in India but have not. But the moment I leave, I become ill. In Kathmandu it was a fever, now it is my stomach. I may have had some bad food or water, or the nervousness of yesterday's 4 hour wait in the Delhi airport for a cancellation, or maybe it was a bug. Whatever, everything came out both ends of my body after hours of painful cramps. Lomotil, bless it, has helped, but I still cannot look a piece of spicy meat in the eye without queasiness.

We ventured out to the airline office and to inquire about tours. Tonight we met 2 girl teachers from Montreal who have spent a year in Europe, now are in Asia for a year. They had spent a month in Iran and loved it. One was engaged to an Iranian, had paratyphoid, whose symptoms sound suspiciously like what I've got.

Bijou is having a hard time with me. She can't stand the sight of vomit and can't help much. It is preventing her own enjoyment because I am sick and can't eat and don't feel like wandering too far away from the head.

Our room is comfortable with modern head, but we wake up at 5 am to prayer call from the minaret. At 6 am the vendor under our window blares the radio until 10-11 p.m..

11 September Wednesday Kabul to Jalalabad to Haddar to Kabul

Finally feeling human we engaged a car along with "Vladimir," a Czech psychiatrist living in New York and went to Jalalabad and Haddar near the Pakistani border.

The ride started through the “suburbs” of Kabul where nomads sleep in tents while sheep and goats graze. There were small villages with mud brick walls and donkeys at the well wheel. Other walls were vacant and ageless, made of the material of the rocky hills and mountains. We went through the rugged pass on the road which was built by Germans. We stopped to view a gorge in which the Kabul River trickled below steep high mountains. We wound through the mountain, barren of green until suddenly we saw a lush valley between the mountains and green rice and corn fields and a deep blue lake—a German built dam. The scenery continued like that—rugged mountains and desert and then a dam—a Russian one then an American one.

The ride started through the “suburbs” of Kabul where nomads sleep in tents while sheep and goats graze. There were small villages with mud brick walls and donkeys at the well wheel. Other walls were vacant and ageless, made of the material of the rocky hills and mountains. We went through the rugged pass on the road which was built by Germans. We stopped to view a gorge in which the Kabul River trickled below steep high mountains. We wound through the mountain, barren of green until suddenly we saw a lush valley between the mountains and green rice and corn fields and a deep blue lake—a German built dam. The scenery continued like that—rugged mountains and desert and then a dam—a Russian one then an American one.

Jalalabad is a small town and near it is Haddar, a walled town, outside of which are digs which reveal a Buddhist monastery 2000 years old, containing sculptures of definite Greek influence. Buddha sits in robes while Greek Gods and Roman senators listen in their togas and uniforms. All of this amazing history was buried in the sand of the centuries until uncovered in 1923. Only recently was it open to the public.

We dined in Jalalabad, parking on the dusty unpaved street, which looks like a cowboy movie town set. Wood store fronts, donkeys and few cars. Men carrying rifles. We ate in a dining hall at a long table. We ordered a big pot of chai; the others ordered various local dishes to eat; my stomach is still gurgling, so I stuck to chai and bread. When the chai came, along with spoons for everyone and the steaming plates of rice, vegetables, meats cubes and red sauce, Vladimir, our medical expert and exuberant raconteur, filled an extra glass with chai and dumped the spoons into the glass to sterilize the eating utensils.

When the food came, the spoons were distributed and diners, including Bijou, ate ravenously. Meanwhile, I crunched the stone-ground bread and glanced at the glass where the spoons had been. The tea in the glass was now black. I dipped in a spoon and when I removed it, it looked like it had been dipped in silver polish: clean up to the hot water level but black above.

I pointed this out to Bijou, who thought it an interesting phenomenon and continued to dip her spoon into the rice dish. I looked around the restaurant, noticing a waiter clear a table by scraping a plate of food into a barrel, dipping the plate and shaking off the excess water, then go into the kitchen and immediately come out with the plate filled for another table of diners.

12 September Thursday Kabul

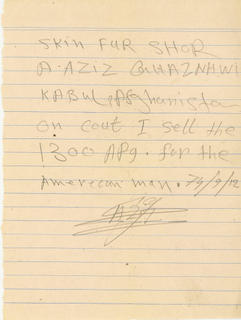

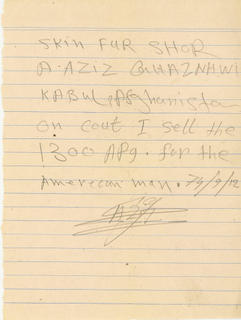

The heat continues to be intense and dry. We spent the day shopping for a coat for Bijou. Afghani sheep and lamb skin and fur, which is hip back in LA. Bijou must have tried on 100 before finding one with the right combination of style, fit and comfort—bargaining made the price about $26. Now she only has to shlep it to Europe. The bargaining and shopping is fun for me ... for a while. But my patience runs dry quickly with the heat. Bijou then bought a hat and when the boy tried to short change us by 1 Afghani, I nearly blew my stack. I sulked most of the afternoon, angry at human nature which cheats, grovels and begs so pitifully.

Afghani sheep and lamb skin and fur, which is hip back in LA. Bijou must have tried on 100 before finding one with the right combination of style, fit and comfort—bargaining made the price about $26. Now she only has to shlep it to Europe. The bargaining and shopping is fun for me ... for a while. But my patience runs dry quickly with the heat. Bijou then bought a hat and when the boy tried to short change us by 1 Afghani, I nearly blew my stack. I sulked most of the afternoon, angry at human nature which cheats, grovels and begs so pitifully.

In the evening our spirits were lifted. We met a couple: a French woman and her Indian husband and son who were in transit to Paris. He spoke 4 Indian languages, French and English. We went with them to the nearby cinema which showed an Indian film.

Our Indian friend translated the dialogue into French for his wife, who whispered it in French to Bijou who whispered it in English to me. After about 10 minutes, I decided it was unnecessary.

It was about a peasant boy who is kidnaped when his father is murdered by a land grabbing lord. He becomes a bandit and pursues a girl and revenge. The film was full of fights, chases, comedy and musical scenes in which the main characters break into operatic song and dance. The stars are zoftig Sophia Loren types, the male stars all round faced. It was marvelous old style movie entertainment

The audience was more entertaining. The men carried long rifles. The women wore their chadris from head to toe and sat apart from the men. The men hooted and cheered the action loudly. The women made that eerie tongue waggling noise that Arab women make. We spent the movie looking around, expecting the men to shoot their rifles at the screen.

13 September Friday Kabul

We went to the Kabul museum this morning. It is supposed to be the one of the world’s unique collections, ethnographically and archeologically speaking. Whatever that means it is probably true. It contains chards of Afghanistan’s checkered past— from all the empires that have attacked, sacked, colonized, converted, passed through or near.

The country itself is a mixture of races—Persian, Pakistani, Indian, Mongol. Rugged mountain tribes and isolated village cultures that have reluctantly succumbed to statehood only in the past century. Everywhere are evidences that these are still rugged, independent primitive people not far removed from the recent tradition of banditry, thievery, and tribal wars (as late as 1929 the “civil war” raged and for months, a bandit usurper controlled the capitol.

In the streets most of which are rock and dust roads, mules and donkeys carry people to market, many parade in unlikely costumes of Pushtan baggy pants and shirts, suit jackets, plastic shoes and distinctive turbans. Women are rarely seen—most wear Islamic chadri (marriages are still arranged here). Rifles are sold in many stores and many carry well used ones. Nomads with shaggy sheep and goats camp close to the town which is surrounded by dry mountains on which mud houses spring from the rock.

In other cliffs in the country, caves dug eons ago are still used by whole tribes. Russians, Americans, Germans have had a hand in aid and China and India look at the maps and see mountain land in military strategy. Pakistan is an uneasy carping neighbor. After seeing the Buddhist, Persian, Greek, Roman, Macedonian, Bactrian and Indian influence in the museum, it is not hard to imagine the far off future with displays of coke bottles and crumbling photos of Chairman Mao.

I have been very busy last night and this morning, covering great mileage ... between my bed and the toilet. I expected to get sick in India but have not. But the moment I leave, I become ill. In Kathmandu it was a fever, now it is my stomach. I may have had some bad food or water, or the nervousness of yesterday's 4 hour wait in the Delhi airport for a cancellation, or maybe it was a bug. Whatever, everything came out both ends of my body after hours of painful cramps. Lomotil, bless it, has helped, but I still cannot look a piece of spicy meat in the eye without queasiness.

We ventured out to the airline office and to inquire about tours. Tonight we met 2 girl teachers from Montreal who have spent a year in Europe, now are in Asia for a year. They had spent a month in Iran and loved it. One was engaged to an Iranian, had paratyphoid, whose symptoms sound suspiciously like what I've got.

Bijou is having a hard time with me. She can't stand the sight of vomit and can't help much. It is preventing her own enjoyment because I am sick and can't eat and don't feel like wandering too far away from the head.

Our room is comfortable with modern head, but we wake up at 5 am to prayer call from the minaret. At 6 am the vendor under our window blares the radio until 10-11 p.m..

11 September Wednesday Kabul to Jalalabad to Haddar to Kabul

Finally feeling human we engaged a car along with "Vladimir," a Czech psychiatrist living in New York and went to Jalalabad and Haddar near the Pakistani border.

The ride started through the “suburbs” of Kabul where nomads sleep in tents while sheep and goats graze. There were small villages with mud brick walls and donkeys at the well wheel. Other walls were vacant and ageless, made of the material of the rocky hills and mountains. We went through the rugged pass on the road which was built by Germans. We stopped to view a gorge in which the Kabul River trickled below steep high mountains. We wound through the mountain, barren of green until suddenly we saw a lush valley between the mountains and green rice and corn fields and a deep blue lake—a German built dam. The scenery continued like that—rugged mountains and desert and then a dam—a Russian one then an American one.

The ride started through the “suburbs” of Kabul where nomads sleep in tents while sheep and goats graze. There were small villages with mud brick walls and donkeys at the well wheel. Other walls were vacant and ageless, made of the material of the rocky hills and mountains. We went through the rugged pass on the road which was built by Germans. We stopped to view a gorge in which the Kabul River trickled below steep high mountains. We wound through the mountain, barren of green until suddenly we saw a lush valley between the mountains and green rice and corn fields and a deep blue lake—a German built dam. The scenery continued like that—rugged mountains and desert and then a dam—a Russian one then an American one.

Jalalabad is a small town and near it is Haddar, a walled town, outside of which are digs which reveal a Buddhist monastery 2000 years old, containing sculptures of definite Greek influence. Buddha sits in robes while Greek Gods and Roman senators listen in their togas and uniforms. All of this amazing history was buried in the sand of the centuries until uncovered in 1923. Only recently was it open to the public.

We dined in Jalalabad, parking on the dusty unpaved street, which looks like a cowboy movie town set. Wood store fronts, donkeys and few cars. Men carrying rifles. We ate in a dining hall at a long table. We ordered a big pot of chai; the others ordered various local dishes to eat; my stomach is still gurgling, so I stuck to chai and bread. When the chai came, along with spoons for everyone and the steaming plates of rice, vegetables, meats cubes and red sauce, Vladimir, our medical expert and exuberant raconteur, filled an extra glass with chai and dumped the spoons into the glass to sterilize the eating utensils.

When the food came, the spoons were distributed and diners, including Bijou, ate ravenously. Meanwhile, I crunched the stone-ground bread and glanced at the glass where the spoons had been. The tea in the glass was now black. I dipped in a spoon and when I removed it, it looked like it had been dipped in silver polish: clean up to the hot water level but black above.

I pointed this out to Bijou, who thought it an interesting phenomenon and continued to dip her spoon into the rice dish. I looked around the restaurant, noticing a waiter clear a table by scraping a plate of food into a barrel, dipping the plate and shaking off the excess water, then go into the kitchen and immediately come out with the plate filled for another table of diners.

12 September Thursday Kabul

The heat continues to be intense and dry. We spent the day shopping for a coat for Bijou.

Afghani sheep and lamb skin and fur, which is hip back in LA. Bijou must have tried on 100 before finding one with the right combination of style, fit and comfort—bargaining made the price about $26. Now she only has to shlep it to Europe. The bargaining and shopping is fun for me ... for a while. But my patience runs dry quickly with the heat. Bijou then bought a hat and when the boy tried to short change us by 1 Afghani, I nearly blew my stack. I sulked most of the afternoon, angry at human nature which cheats, grovels and begs so pitifully.

Afghani sheep and lamb skin and fur, which is hip back in LA. Bijou must have tried on 100 before finding one with the right combination of style, fit and comfort—bargaining made the price about $26. Now she only has to shlep it to Europe. The bargaining and shopping is fun for me ... for a while. But my patience runs dry quickly with the heat. Bijou then bought a hat and when the boy tried to short change us by 1 Afghani, I nearly blew my stack. I sulked most of the afternoon, angry at human nature which cheats, grovels and begs so pitifully.In the evening our spirits were lifted. We met a couple: a French woman and her Indian husband and son who were in transit to Paris. He spoke 4 Indian languages, French and English. We went with them to the nearby cinema which showed an Indian film.

Our Indian friend translated the dialogue into French for his wife, who whispered it in French to Bijou who whispered it in English to me. After about 10 minutes, I decided it was unnecessary.

It was about a peasant boy who is kidnaped when his father is murdered by a land grabbing lord. He becomes a bandit and pursues a girl and revenge. The film was full of fights, chases, comedy and musical scenes in which the main characters break into operatic song and dance. The stars are zoftig Sophia Loren types, the male stars all round faced. It was marvelous old style movie entertainment

The audience was more entertaining. The men carried long rifles. The women wore their chadris from head to toe and sat apart from the men. The men hooted and cheered the action loudly. The women made that eerie tongue waggling noise that Arab women make. We spent the movie looking around, expecting the men to shoot their rifles at the screen.

13 September Friday Kabul

We went to the Kabul museum this morning. It is supposed to be the one of the world’s unique collections, ethnographically and archeologically speaking. Whatever that means it is probably true. It contains chards of Afghanistan’s checkered past— from all the empires that have attacked, sacked, colonized, converted, passed through or near.

The country itself is a mixture of races—Persian, Pakistani, Indian, Mongol. Rugged mountain tribes and isolated village cultures that have reluctantly succumbed to statehood only in the past century. Everywhere are evidences that these are still rugged, independent primitive people not far removed from the recent tradition of banditry, thievery, and tribal wars (as late as 1929 the “civil war” raged and for months, a bandit usurper controlled the capitol.

In the streets most of which are rock and dust roads, mules and donkeys carry people to market, many parade in unlikely costumes of Pushtan baggy pants and shirts, suit jackets, plastic shoes and distinctive turbans. Women are rarely seen—most wear Islamic chadri (marriages are still arranged here). Rifles are sold in many stores and many carry well used ones. Nomads with shaggy sheep and goats camp close to the town which is surrounded by dry mountains on which mud houses spring from the rock.

In other cliffs in the country, caves dug eons ago are still used by whole tribes. Russians, Americans, Germans have had a hand in aid and China and India look at the maps and see mountain land in military strategy. Pakistan is an uneasy carping neighbor. After seeing the Buddhist, Persian, Greek, Roman, Macedonian, Bactrian and Indian influence in the museum, it is not hard to imagine the far off future with displays of coke bottles and crumbling photos of Chairman Mao.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)